In this interview, AZoQuantum speaks with David Roy-Guay, CEO and Founder of SBQuantum, about the development of quantum diamond magnetometer technology and its growing role in navigation, Earth observation, and object detection.

Could you introduce yourself, and your role at SBQuantum?

I’m the CEO and founder of SBQuantum. My background is quantum physics and I did my PhD at the Institut Quantique in Sherbrooke near Montreal, working on impurities in diamond. Toward the end of my PhD, I decided to take the technology out of the lab, started working with electrical engineers, and began prototyping something portable that we can take in the field.

We went through the Creative Destruction Lab quantum stream in Toronto, and more recently the mining stream, to refine who our target customers are and where we can have impact. We’ve embraced open innovation across mining, space, and environmental applications. We’ve also worked with the Canadian Defence Forces, and early on we moved beyond hardware into algorithms, to create value for end users who are not magnetic sensing specialists.

We have a sensor that plugs directly into a CubeSat, and it’s scheduled to launch in March 2026.

SBQuantum team members working at the company's labs in Sherbrooke, Quebec. Image Credit: SBQuantum

Please explain what a quantum diamond magnetometer is, and the nature of your solution, in particular the sensors and algorithms you offer?

Diamond-based magnetometers are a hot topic in quantum sensing because they operate at room temperature, provide vector information on magnetic fields, and offer driftless readings that are hard to match with classical sensors.

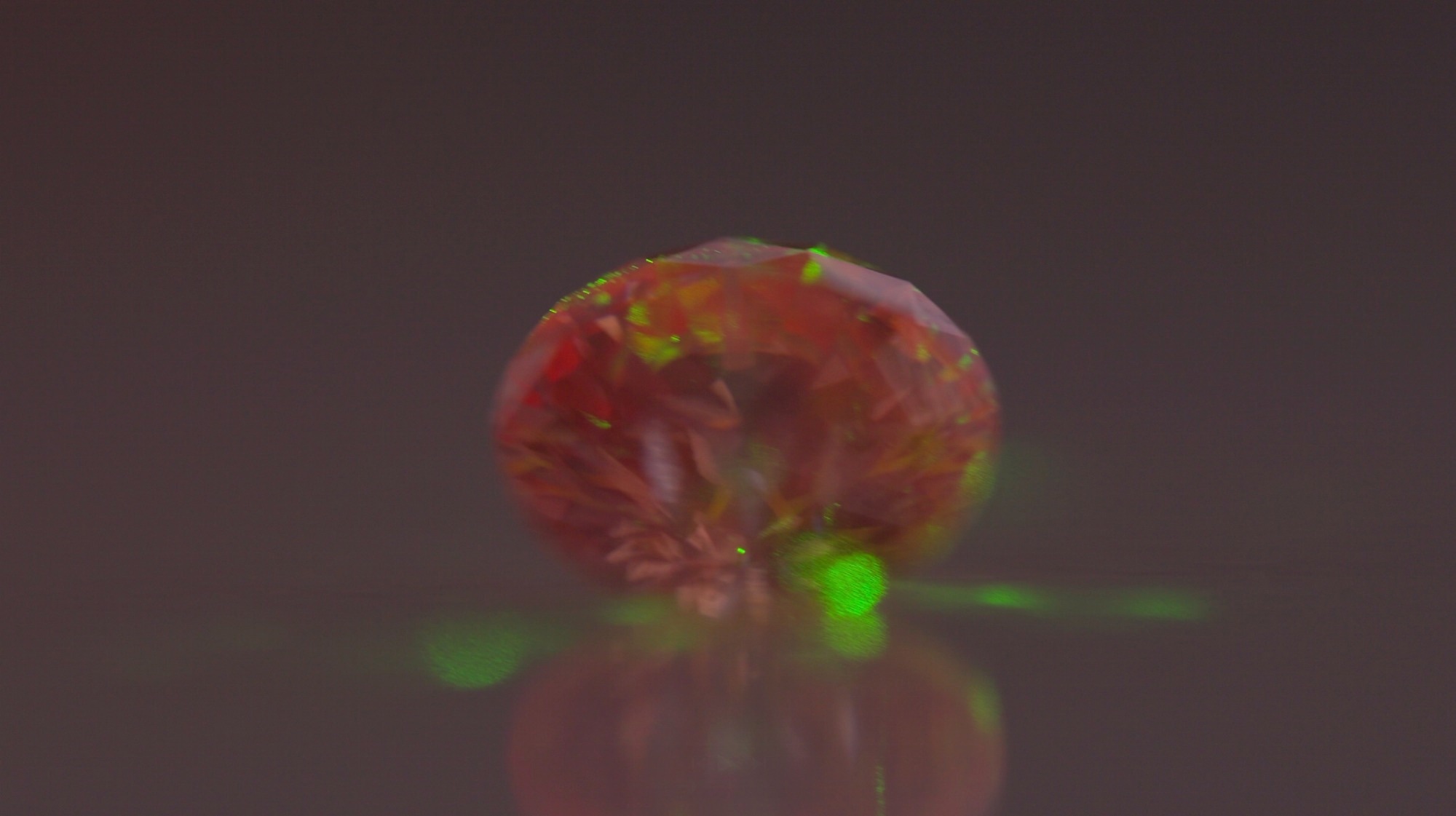

At a high level, we take a synthetic diamond containing billions of quantum impurities. Specifically, there’s a nitrogen atom next to a vacancy in the lattice. That defect frees up electrons with a quantum spin property. You can think of that spin as a tiny magnet that we use to measure the magnetic field precisely.

We excite the defect with a green laser and collect red light. The red light fluctuates with the magnetic field strength and direction. The base method is optically detected magnetic resonance: green laser excitation, red light collection, and resonant microwaves that create a measurable resonance response. We track those resonance lines and convert them into the magnetic field vector, with strong calibration because the physics is well described.

The vector is important because magnetic sensing “sees” everything around the sensor. A car passing by, someone carrying a laptop, or someone carrying a rifle can create similar signals. By measuring the vector field and using an array of four sensors, you can infer where the field is coming from and estimate speed and mass. Our algorithms distill that into outputs like object location and classification, instead of forcing the user to interpret wiggly lines.

A nitrogen-vacancy center diamond glows red when excited by microwave pulses and SBQuantum's green laser. Image Credit: SBQuantum

Could you explain what your new partnership with ESA entails? What is the aim of the mission, and how will it help future navigation tools?

We won the ESA contract through a bidding process across European countries. The objective is to prototype a diamond-based magnetometer with performance sufficient for Earth observation. For us, it’s a great program because it drives a major performance leap: roughly tenfold improvement in sensitivity and accuracy, and about a tenfold increase in bandwidth, while keeping a similar size, weight, and power profile.

It means rethinking electronics, quantum control, and readout schemes so we can hit those metrics. The mission focus is understanding Earth’s dynamics, especially the core magnetic field created by circulating magma. The North Pole is moving and accelerating, and that impacts navigation systems. The global magnetic field map used to be updated every 10 years, now it’s every five years because of this trend. In extreme cases, places have even had to repaint runway numbers because magnetic north shifted enough to matter.

There are also broader Earth observation applications. Magnetic fields allow you to look at different layers: core, crustal contributions, and even signals linked to ocean currents. You can’t measure temperature at depth directly with magnetics, but if there’s a big enough moving body of ions, you can detect currents at depth. A classic example is the Gulf Stream. There’s also interest in monitoring the ionosphere, where electromagnetic events can disrupt GPS and communications. A precise sensor in orbit can help track these phenomena over time.

What applications can you see for this technology? What industries stand to benefit from it?

Magnetometers have existed for decades and were popularized for anti-submarine warfare, but at the end of the day it’s a compass, and you can apply it anywhere you need to measure magnetic fields. We looked at 27 application verticals, from navigation, to underwater and underground inspection, to even trying to count fish in aquaculture.

Key areas include exploration and mining, where you can estimate resources and help geologists decide where to drill for critical minerals. There’s defence, including detecting submarines using the magnetic anomaly they create in Earth’s field. There are health applications, like detecting cancer cells functionalized with magnetic material at very low thresholds. Some groups are looking at microelectronics inspection for faults, and infrastructure inspection such as finding cracks in aircraft wings or defects and corrosion in nuclear power pipes.

For SBQuantum, we chose to focus on public safety, and the space work is also valuable because it matures and demonstrates the technology. Long term, better magnetic maps could enable more robust magnetic navigation.

Could you run us through the key milestones and performance metrics you are targeting to deliver on your second ESA contract?

Our approach is systems engineering-driven. We reduce the key risks we’ve identified to improve performance. We’re currently in the breadboarding phase, demonstrating the subsystems needed to hit a target metric around 200 picotesla, which is about 10 times better than what we have now. Sensitivity needs to be on the order of 100 picotesla to measure very small fluctuations, like magnetic fields from ocean currents or changes in the core field.

To get there, we’re designing new optical systems to collect more red light, since sensitivity scales with the square root of collected intensity. We’re also improving readout electronics by minimizing noise and developing schemes to operate with greater accuracy. Today we use a biasing scheme based on magnets for vector measurements, but those can drift over time, and we’re aiming for very high precision: Earth’s field is roughly 50,000 nanotesla, and we want to measure it with around 100 picotesla accuracy, which is challenging. So we are changing the biasing to a dynamic one, effectively canceling out any electronics drift.

After breadboarding, we move into engineering the final electronics and production, then qualification testing in Canada at our geomagnetic observatory. We are also exploring testing infrastructure in Europe, including work we’ve done with the British Geological Survey.

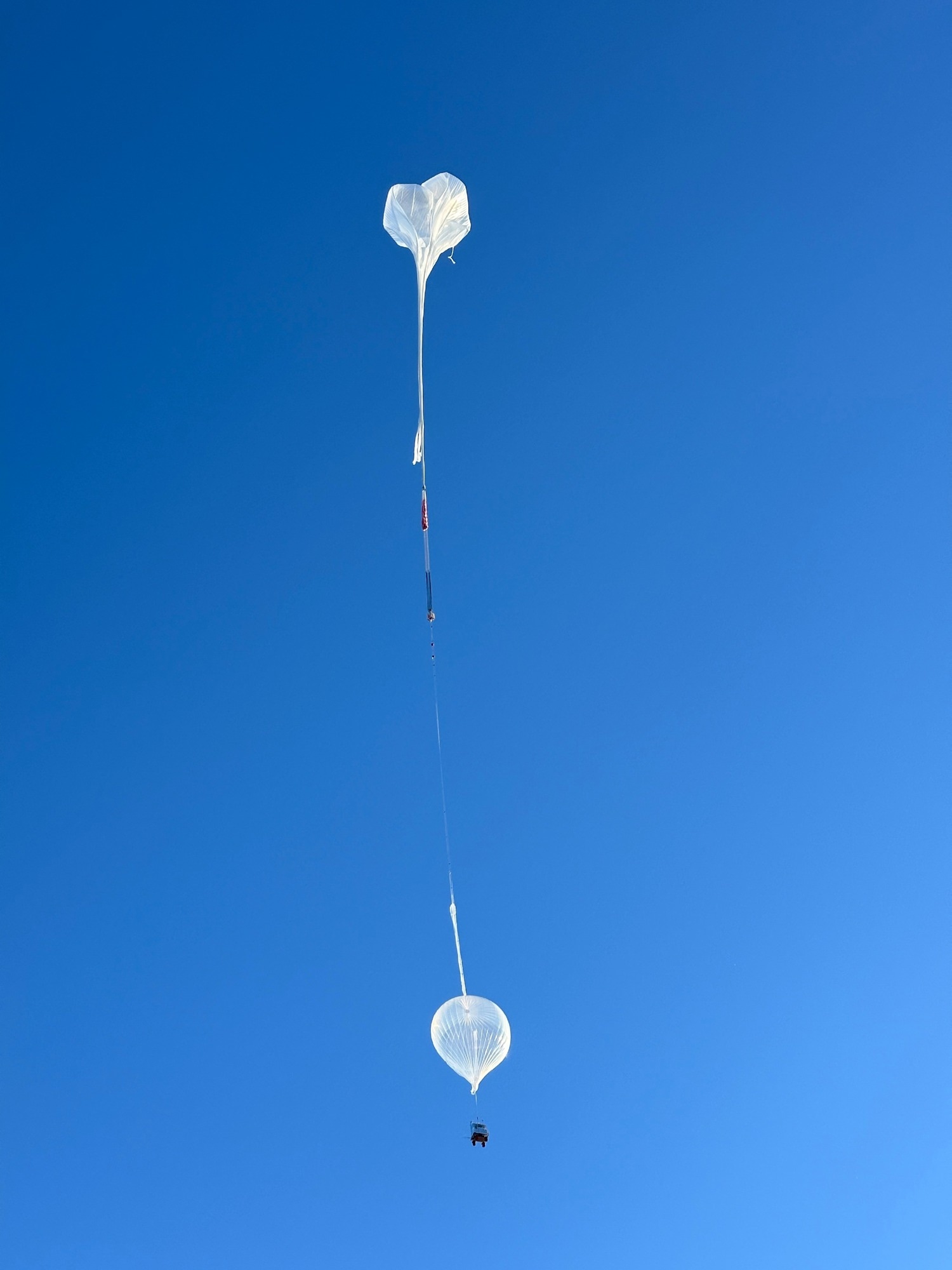

SBquantum's quantum magnetometer deployed for testing on a low-earth-orbit balloon launched from the Esrange Space Centre in Northern Sweden. Image Credit: SBQuantum

What hardening, thermal management, and calibration strategies have you implemented to maintain sensitivity and stability over mission lifetime?

There’s a long list of tests for space qualification. The advantage of diamond technology is that it’s almost made for space, in the sense that these diamond vacancies are created using very high-energy beams, so radiation conditions in space are relatively easy from the diamond’s perspective. We still have to qualify the surrounding electronics for radiation in low Earth orbit, and we’ve done that and shown it’s okay.

A critical subsystem is the laser. Radiation can affect semiconductor laser dopants and shift the lasing wavelength. In our case, we use non-resonant excitation, so wavelength shifts do not significantly impact performance. That’s a big advantage. Same happens with thermal fluctuations, we simultaneously measure the diamond temperature and the subsystems thermal drift doesn't impact the quantum physics description, hence the system is tolerant. We don’t expect sensitivity to degrade dramatically over time based on what we’ve characterized so far, and we can recalibrate using the fundamental properties of the system.

In orbit, we also recalibrate for satellite effects. The sensor is mounted near batteries and metal elements that can create noise, so as the satellite orbits, we recalibrate periodically to preserve stability over time.

What data do you hope to collect to design and develop your future solutions?

For space applications, we’d love to deploy a few satellites so we can build a more complete 3D understanding of the contributors to Earth’s magnetic field: the core field, crustal field, and ionospheric and atmospheric contributions. We also want to reach the sensitivity needed to image the evolution of ocean currents, because there isn’t really another practical way to do that today without deploying tens of thousands of buoys and collecting measurements, which is tedious.

We also want to refine magnetic field maps from space, including in the Arctic. The Arctic is becoming more contested as new routes open, and it’s also where the magnetic field evolves the most. Tracking that with higher precision could support navigation for autonomous platforms in the long run.

Any concluding words?

We’re proud to be supported by ESA. For us, it’s great to see the technology deployed in the field and adopted in different environments, some harsher than others. It’s exciting that quantum sensing is at that stage. We’re eager to keep refining the technology and finding new applications in space, defence, and navigation. The future looks bright for these kinds of quantum sensors, and we’re happy to be part of it.

Want to know more about quantum sensing? Read on here

About the Speaker

David Roy-Guay is the Founder and CEO of SBQuantum, where he leads a multidisciplinary team advancing cutting-edge diamond-based quantum magnetometry. Combining deep scientific expertise - supported by 6+ patents, 10 scientific publications, and a PhD in physics - with strategic leadership, he has secured over $15M in grants and R&D contracts while guiding collaborations with ESA, NASA, the NGA, and major defense primes. A co-inventor of multiple quantum sensing technologies and architect of the first diamond-based magnetometer CubeSat payload, he is recognized for transforming complex

quantum research into practical, user-centric solutions and for steering SBQuantum’s growth at the forefront of Magnetic Intelligence innovation, spanning aerospace, defense and public safety.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited (T/A) AZoNetwork, the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and Conditions of use of this website.