Researchers from the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology (OIST) and the University of Oklahoma have pinpointed a one-dimensional system where such particles can exist and have examined their theoretical characteristics. The study was published in Physical Review A.

Image Credit: Jack Featherstone

Image Credit: Jack Featherstone

Physicists have traditionally categorized all elementary particles in our three-dimensional universe as either bosons or fermions. Bosons typically serve as force carriers, like photons, while fermions make up the fundamental components of matter, including electrons, protons, and neutrons.

However, at lower dimensions of space, the clean categorization begins to fail. Since the 1970s, a third class capturing anything in between a fermion and a boson, named anyon, has been expected to exist, and in 2020, these strange particles were found experimentally at the interface of supercooled, strongly magnetized, one-atom thick (that is, two-dimensional) semiconductors.

Thanks to recent advances in experimental control over single particles in ultracold atomic systems, these studies also pave the way for exploring the fundamental physics of tunable anyons in realistic experimental conditions.

Every particle in our universe seems to fit strictly into two categories: bosonic or fermionic. Why are there no others? With these works, we’ve now opened the door to improving our understanding of the fundamental properties of the quantum world and it’s very exciting to see where theoretical and experimental physics take us from here.

Thomas Busch, Professor, Quantum Systems Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

Breaking the Boson/Fermion Binary

The elementary classification is based on how two identical particles react when they switch positions. Experimental evidence suggests a strict binary in three dimensions: particles either remain unchanged, like bosons, or their system undergoes a full inversion, as with fermions. So far, no other behavior has been observed.

This binary is based on quantum physics' fundamental notion of indistinguishability. In classical physics, if you paint two identical marbles red and blue, it is possible to tell them apart even if they are switched.

However, at the quantum level, two identical particle (for example electrons) cannot be painted red or blue. If their quantum qualities are the same, they cannot be discriminated. As a result, if they exchange places, their new configuration is physically indistinguishable from the old.

Furthermore, because the physical state must remain constant, the quantifiable characteristics of this two-particle system cannot change.

Because this exchange is equivalent to doing nothing, the mathematical statistics governing the event, known as the exchange factor, must obey a simple rule: the square of the exchange factor must be equal to 1. The only two numbers that satisfy this rule are +1 and -1. That’s why all particles must be, respectively, bosons, for which the factor is 1, or fermions, for which the factor is -1.

Raúl Hidalgo-Sacoto, PhD Student, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

This categorization has physical ramifications. Bosons tend to behave uniformly: consider lasers, where photons of the same wavelength (color) travel in sync with one another, or Bose-Einstein condensates, where ultracold atoms adopt the same state. Fermions, on the other hand, are antisocial: electrons, protons, and neutrons cannot exist in the same state, which is why we have a periodic table with various elements.

If there are only two types of particles in three dimensions, how come more can arise in lower dimensions? The reason for this is that the particles have fewer options for wiggling around one another, and when they cross paths (when they change places) the exchange becomes braided in space and time, implying that the particles cannot be untangled, and thus the new state is no longer indistinguishable from the previous one.

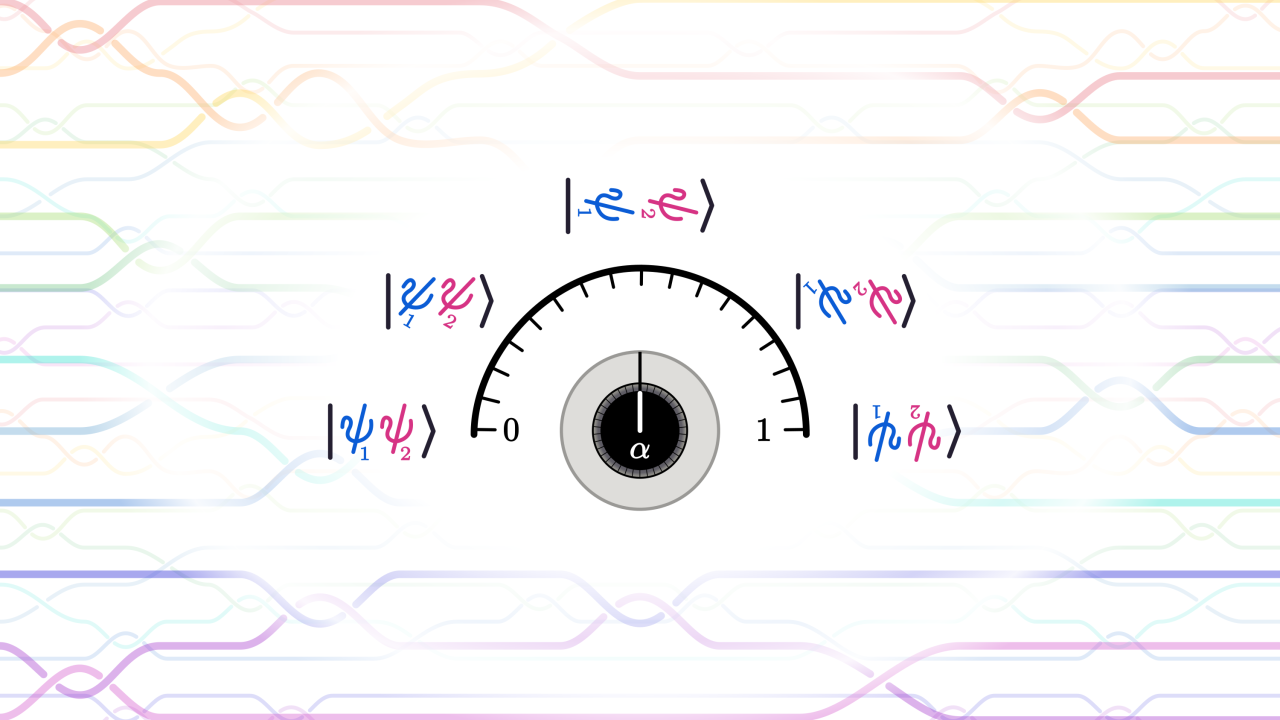

In lower dimensions, this exchange is no longer topologically equivalent to doing nothing. To satisfy the law of indistinguishability, we need exchange factors over a continuous range to account for the exchange, dependent on the exact twists and turns of the paths.

Raúl Hidalgo-Sacoto, PhD Student, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology

As a result, a new class of particles that capture particles with exchange factors other than +1 or -1 might exist: anyons, which are neither bosons nor fermions.

A Recipe for Adjustable Anyons

Hidalgo-Sacoto and colleagues published studies demonstrating that in 1D space, the binary remains broken with the intriguing addition of a directly controllable exchange factor. In 1D, particles cannot switch positions simply by going around each other; instead, they must pass through one another.

As a result, the exchange factor in three dimensions behaves quite differently from what’s seen in higher-dimensional systems. Research suggests this difference is closely tied to the strength of the short-range contact interactions between particles.

Experimentally, this enables fine-grained control over the ensuing exchange statistics, implying a plethora of intriguing experiments and questions to be posed and answered.

“We’ve identified not only the possibility of existence of one-dimensional anyons, but we’ve also shown how their exchange statistics can be mapped, and, excitingly, how their nature can be observed through their momentum distribution. The experimental setups necessary for making these observations already exist. We’re thrilled to see what future discoveries are made in this area, and what it can tell us about the fundamental physics of our universe,” summarized Prof. Busch.

Journal References:

Hidalgo-Sacoto, R., et al. (2026) Two identical one-dimensional anyons with zero-range interactions: Exchange statistics, scattering theory, and anyon-anyon mapping. Physical Review A. DOI: 10.1103/h2vs-ll9d. https://journals.aps.org/pra/abstract/10.1103/h2vs-ll9d

Hidalgo-Sacoto, R., et al. (2026) Universal momentum tail of identical one-dimensional anyons with two-body interactions. Physical Review A. DOI: 10.1103/zf6z-2jjs. https://journals.aps.org/pra/abstract/10.1103/zf6z-2jjs