Mohammad Hafezi, a Joint Quantum Institute Fellow, and his colleagues investigated how changing the ratio of fermionic to bosonic particles in a material affects its interactions. In a study that was published in the journal Science on January 1st, 2026, the researchers discussed their findings and tests.

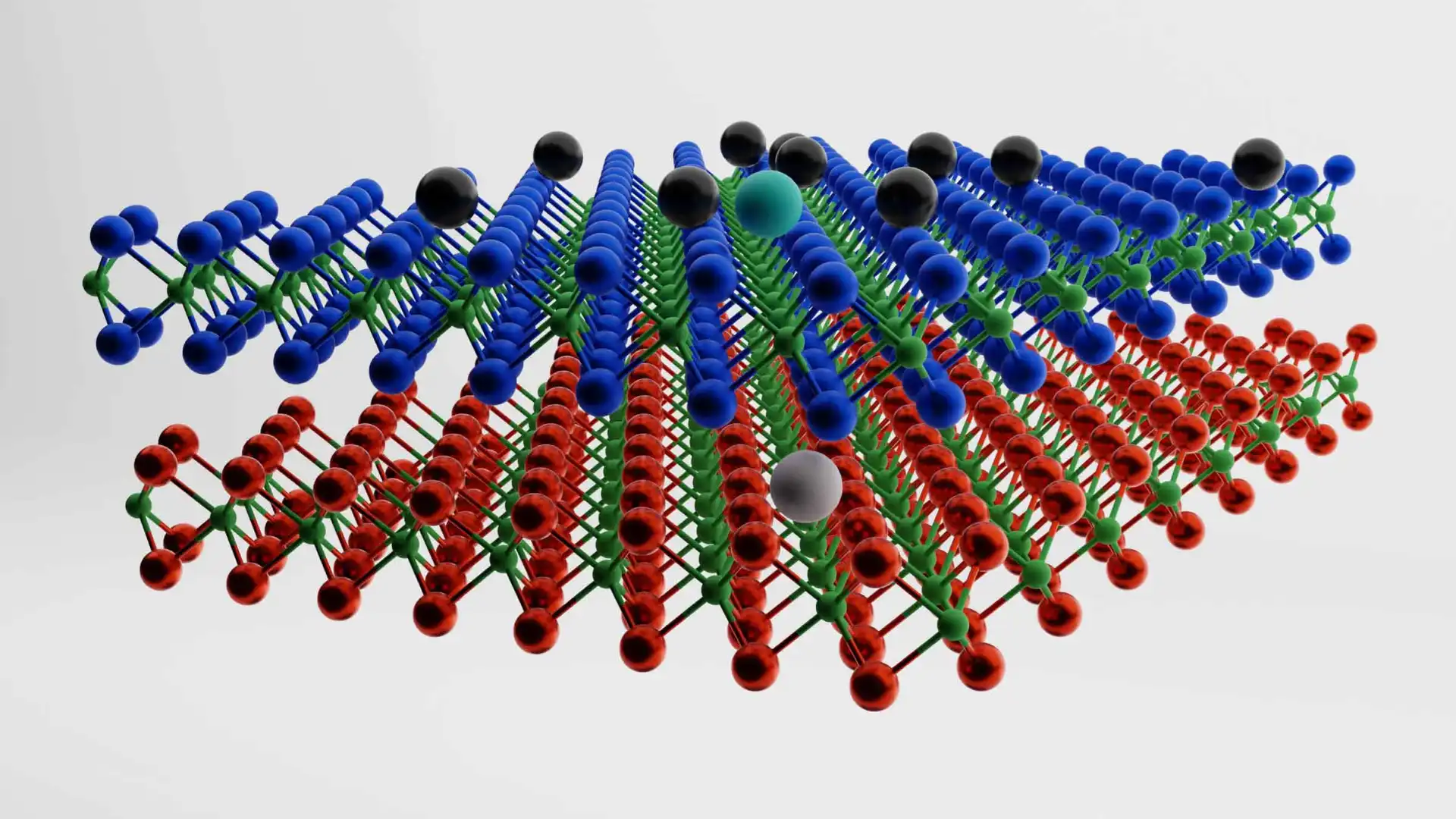

An exciton forms when an electron pairs up with a hole (a mobile particle-like void in a material where an electron is missing from an atom). When paired up as an exciton, a hole and electron normally travel around together as an exclusive couple, but a new experiment probes what happens when conditions in a material break up the pair. In the image, a hole (grey sphere) resides in the bottom layer of a stacked material and is paired to an electron in the top layer (cyan sphere). None of the electrons present in the top layer (black spheres) are willing to share a spot in the material with each other or the electron in the exciton. Image Credit: Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI

An exciton forms when an electron pairs up with a hole (a mobile particle-like void in a material where an electron is missing from an atom). When paired up as an exciton, a hole and electron normally travel around together as an exclusive couple, but a new experiment probes what happens when conditions in a material break up the pair. In the image, a hole (grey sphere) resides in the bottom layer of a stacked material and is paired to an electron in the top layer (cyan sphere). None of the electrons present in the top layer (black spheres) are willing to share a spot in the material with each other or the electron in the exciton. Image Credit: Mahmoud Jalali Mehrabad/JQI

In a sense, quantum particles have a kind of social behavior. One of their most important traits is whether they act more like extroverts (bosons) or introverts (fermions) because this determines how they interact and group together.

Extroverted bosons are perfectly happy to share the same quantum state, which gives rise to striking phenomena like superconductivity and superfluidity. In contrast, introverted fermions refuse to occupy the same quantum state, a fundamental behavior that makes the formation of solid matter possible in the first place.

But the social lives of quantum particles go beyond simply being fermions or bosons. These particles interact in complex ways that shape the materials we observe, and understanding these interactions is key to explaining why materials behave the way they do. For instance, electrons may become tightly bound to individual atoms in a material, leading to insulating behavior.

In other cases, electrons move freely throughout the material, a hallmark of conductors. Sometimes, they even pair up in stable formations called Cooper pairs, enabling superconductivity. These quantum-level interactions not only define a material’s properties but also underpin technologies ranging from everyday electrical wiring to advanced lasers and solar panels.

They anticipated fermions to avoid both each other and the bosonic counterparts chosen for the experiment, they projected that huge swarms of fermions would obstruct bosons' movement. The experiment demonstrated the exact opposite: when the researchers tried to freeze the bosons in place with a fermion blockade, the bosons began to move swiftly.

We thought the experiment was done wrong. That was the first reaction.

Daniel Suárez-Forero, Assistant Professor, University of Maryland

However, after a thorough review of their findings, the researchers reached a conclusion. They had uncovered a way to host a kind of quantum party, one where particles set aside their usual social rules, leading to a dramatic (and potentially useful) shift in behavior .

The group's experiment looked at how electrons interact with one another as well as couples made up of electrons and holes. Holes, unlike electrons, are not fully actual particles. Instead, they are quasiparticles, which act like particles but exist only as a disturbance in the surrounding medium.

A hole occurs when one of a material's atoms loses an electron, resulting in an unbalanced positive charge. The hole can move about and convey energy within the material, but it cannot escape. If an electron goes into a hole, it disappears.

Sometimes electrons and holes create an atom-like configuration (with the hole acting as a proton). When this occurs, the hole and electron interact as a single quantum entity known as an exciton. It generally takes energy to break apart the particles in an exciton, therefore when an exciton travels, the hole and electron almost always remain together. This characteristic prompted scientists to describe the exciton connection as “monogamous.”

The composite excitons are bosons, whereas individual electrons are fermions. Together, the two made an appropriate cast for the group's investigations on fermion and boson interactions.

At least this was what we thought. Any external fermion should not see the constituents of the exciton separately; but in reality, the story is a little bit different.

Tsung-Sheng Huang, Postdoctoral Researcher, Institute of Photonic Sciences

To obtain the particles they need and an appropriate method of controlling them, the researchers developed a material with the properties required for their experiment by carefully aligning a layer of one thin material on another thin material with precisely the exact alignment.

The material's qualities made it easy to make excitons that survive for a long period, while its structure kept things organized by giving a clean grid of spaces where an exciton or an unpartnered electron needed to be.

The structure makes electrons and excitons experience the material more like a restaurant set up for Valentine’s Day (intimate tables spread across the floor) rather than a packed, standing-room-only concert hall. Every exciton and solitary electron must find a seat at a table, and the introverted electrons refuse to share, whether with each other or with excitons.

Excitons, however, aren’t content to stay put. They tend to move around, but instead of crossing the room directly, they quietly hop from one nearby empty table to another. This subtle movement sometimes leads to inefficient detours, especially when navigating around clusters of occupied tables.

In an experiment, the researchers can host trillions of particles in the material's seating arrangement and regulate the number of excitons and electrons that are free to move through the room. The researchers use various electrical voltages to push electrons into or out of the material to add or remove electrons.

They call forth excitons from the current substance to add them. The material's atoms will absorb the light when the researchers flash a certain color laser on it. Excitons are produced when the laser's energy removes electrons from the atoms.

The researchers were able to monitor the final destination of the excitons they produced by simply keeping an eye out for any indications of their eventual demise. The excess energy held by an exciton must finally be released as light when its electron and hole merge.

This light was gathered by the researchers and utilized as a marker for the excitons' ultimate placements. Despite not being able to observe each exciton cluster's unique journey, this allowed them to calculate the amount that each cluster of excitons diffused through the material.

We can basically do any ratio. We can populate the system with only bosons, only fermions, or any ratio. And the diffusivity, the way in which the bosons move, changes a lot depending on the number of particles of each species.

Daniel Suárez-Forero, Assistant Professor, University of Maryland

During the experiment, the researchers altered the electron density consistently and deduced as much as they could from the variations in boson diffusion. They exploited the mobility of the excitons to determine their interactions with the electrons and one another, transforming each group of excitons into an experimental sensor.

When there were few electrons, the researchers anticipated them to never come into contact and so have no impact on each other or the excitons. In contrast, plentiful electrons are predicted to avoid each other and block excitons.

Things began as expected, with excitons moving shorter and shorter distances as the electron population increased. Excitons were increasingly forced to take a winding path around electrons rather than a generally straight path.

The experiment eventually progressed to the point where an electron occupied nearly every table. The researchers anticipated this to effectively prevent exciton diffusion, but instead saw a sharp increase in exciton mobility. Despite the fact that the excitons' pathways should have been restricted, they traveled considerably farther.

No one wanted to believe it. It’s like, can you repeat it? And for about a month, we performed measurements on different locations of the sample with different excitation powers and replicated it in several other samples.

Pranshoo Upadhyay, Study Lead Author and Graduate Student, Joint Quantum Institute

They even attempted the experiment in a separate lab after Suárez-Forero finished his postdoctoral studies at JQI and worked as a research scientist at the University of Geneva.

“We repeated the experiment in a different sample, in a different setup, and even in a different continent, and the result was exactly the same,” Suárez-Forero added.

They also needed to ensure that they were not misinterpreting the results. They were simply seeing exciton diffusion, not the interactions themselves. They were depending on mathematical theories to explain the results, and they wanted to ensure that no errors were hidden in their calculations.

To find out what was going on, the team worked closely together on both theoretical and experimental levels.

“We spent months going back and forth with theorists, trying out different models, but none of them captured all our experimental observations. Eventually, we realized that the excitons sit differently than the free electrons and holes in our system. That was the turning point - when we began thinking of the exciton beyond monogamy,” Upadhyay further added.

The team believed that the extremely crowded surroundings were causing the excitons to abandon monogamy, therefore the researchers dubbed the process “non-monogamous hole diffusion.” Essentially, the unanticipated result occurred when the experimenters inundated the material (the metaphorical restaurant) with electrons, each demanding a table for themselves.

The researchers discovered that when the population of available electrons became sufficiently unbalanced, the holes in each exciton perceived all other electrons as similar to the one they were already with; the regular rule of exciton monogamy broke down.

The fast diffusion was driven by holes unexpectedly abandoning their long-term electron companions. Instead of moving from table to table with the same electron, the holes were speed dating with electron after electron, allowing each exciton to make a direct path to its destination. Without the typical twisting path around all of the single electrons, each exciton traveled significantly further before emitting its trademark flash of annihilation.

To induce this lopsided dating pool and quick travel, the researchers simply adjusted the voltage. Existing devices can easily control voltages; therefore, the technology has a wide range of applications in future experiments and technologies that use excitons, such as some solar panel designs.

The researchers are already applying their understanding of how excitons and electrons interact to analyze other studies. They are also attempting to use their new understanding of these materials to gain better control over the quantum interactions that they can cause in experiments.

Suárez-Forero concluded, “Gaining control over the mobility of particles in materials is fundamental for future technologies. Understanding this dramatic increase in the exciton mobility offers an opportunity for developing novel electronic and optical devices with enhanced capabilities.”

This study was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the Simons Foundation.

Journal Reference:

Upadhyay, P. et.al. (2025) Giant enhancement of exciton diffusion near an electronic Mott insulator. Science. Doi: 10.1126/science.ads5266. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.ads5266