Quantum chaos lives in the uneasy space between two extremes: the wild unpredictability of classical chaos and the perfectly deterministic evolution of quantum mechanics. New results from realistic quantum hardware now suggest that this chaos, and the rapid error growth it brings, may emerge much earlier than designers ever expected.1

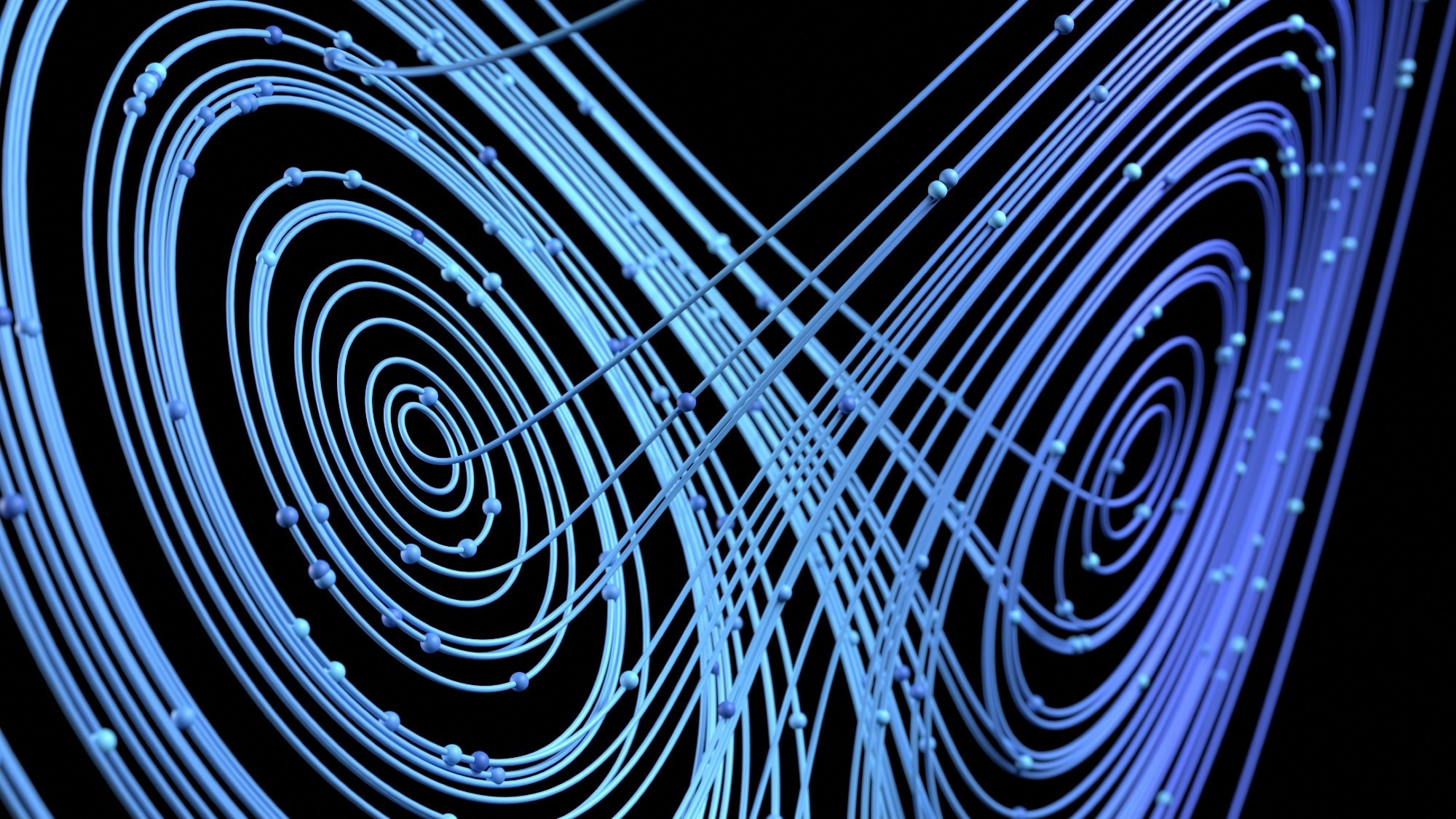

Image Credit: Ricardo Javier/Shutterstock.com

What is Quantum Chaos?

In classical mechanics, a system is considered chaotic when its trajectories in phase space are highly sensitive to initial conditions. Even two nearly identical starting points will diverge over time according to:

δx(t) ∼ eλt δx(0),

where λ is the Lyapunov exponent, a measure of how quickly nearby trajectories separate. Common examples of chaotic systems include weather patterns and coupled pendulums.2

Quantum mechanics, in contrast, is governed by the linear and deterministic Schrödinger equation. Unlike classical systems, there are no phase-space trajectories in the traditional sense, and distances between wavefunctions in Hilbert space don’t grow exponentially over time. This makes the concept of “quantum chaos” more subtle, as classical definitions don’t carry over directly.2-3

Instead, quantum chaos is diagnosed indirectly. Spectral statistics reveal that the energy levels of a quantum chaotic system show the same correlations as random matrices, which is the content of the Bohigas–Giannoni–Schmit conjecture.3

The eigenstate thermalization hypothesis (ETH) suggests that individual many-body eigenstates already contain thermal properties, providing a framework for understanding how isolated quantum systems can thermalize. To probe chaotic behavior dynamically, researchers now commonly use tools like out-of-time-order correlators (OTOCs), entanglement growth, and operator spreading, all of which have become standard indicators of quantum chaos.4

Altland and Sonner show that, at late times, chaotic systems are universally described by an effective field theory whose fluctuations reproduce the characteristic “ramp” and “plateau” of random matrix spectral statistics, thereby giving a precise microscopic meaning to quantum chaos in terms of spectral correlations and long-time dynamics.2

This matters because quantum chaos is not merely an aesthetic property of spectra: it governs thermalization in many body systems such as cold atoms, nuclei, and mesoscopic conductors; information scrambling in systems with holographic duals, including black hole models; and the limits of quantum computing, where uncontrolled chaos can rapidly destroy the structure of quantum information.4

Keep quantum chaos in check by downloading the PDF of the article

The New Research: Chaos Comes Early

A recent study by Börner et al., from the University of Cologne in collaboration with RWTH Aachen University and the Peter Grünberg Institute in Germany, tackles a very concrete question: how close are present day superconducting quantum processors to chaotic dynamical regimes?5

They consider arrays of transmon qubits, the workhorse of superconducting quantum computing. A transmon is essentially a nonlinear quantum pendulum realized with a Josephson junction and a capacitor. When many transmons are capacitively coupled, the resulting device is mathematically equivalent to a lattice of coupled nonlinear oscillators, precisely the sort of system that exhibits classical chaos.5

The authors take the classical limit of this hardware model (formally setting ?→0) and study the resulting network of coupled pendula. They compute Lyapunov exponents as measures of classical instability, and, for small systems of up to about ten transmons, compare these to fully quantum simulations, where chaos is quantified via inverse participation ratios (IPRs), measures of how broadly a quantum state spreads over the many-body basis.5

The surprising finding is about where chaos appears:

- For two transmons, chaos exists only at very high energies, far above the levels used to encode qubits.

- For chains of around ten transmons, however, chaotic behaviour “bleeds down” into the energy range corresponding to the computational qubit subspace. In other words, once enough qubits are coupled, chaotic resonances can appear already at low excitations relevant for quantum computing.

Classical simulations can then be scaled to hundreds or even thousands of transmons, including realistic layouts for IBM’s Falcon, Osprey and Condor chips, far beyond what can be quantum-simulated on classical computers. The authors find that Lyapunov exponents systematically increase with system size, and conclude that “larger layouts require added efforts in information protection.”5

Taken together with Leone et al.’s work on chaotic quantum circuits, which shows that genuine quantum chaos requires a number of non-Clifford gates scaling as (Θ(N)) with qubit number, the picture is that both at the hardware level (transmon arrays) and the gate level (quantum circuits) chaos can become relevant already at relatively modest system sizes.6

Implications for Quantum Technologies

The early onset of chaos poses serious challenges for coherent quantum computation. In chaotic regimes, even small perturbations, like fabrication imperfections, stray couplings, or slight detuning errors, can be rapidly amplified. Within the transmon framework, chaotic dynamics give rise to long-range correlations and effective multi-qubit interactions, such as unwanted ZZ couplings. These effects accelerate decoherence and increase leakage out of the computational subspace, undermining the fidelity of quantum operations.6

In circuit language, Leone et al. show that once a circuit contains (Θ(N)) non-Clifford gates, it behaves like a unitary 4-design: it reproduces high-order moments of the Haar random ensemble, a signature of essentially maximal quantum chaos. In this regime, errors propagate extremely fast: a local fault is quickly spread over many qubits.6

From a more optimistic angle, chaos is also what makes some quantum systems powerful scramblers of information. Fast growth of entanglement and decay of OTOCs are precisely the features exploited in models of black-hole dynamics and in holographic dualities, where quantum chaotic systems mimic gravitational physics. Altland and Sonner’s effective field theory, for example, provides a bridge between random-matrix universality and late-time behaviour in AdS/CFT dual pairs.

Early chaos in realistic hardware suggests that black-hole-like scrambling might be achievable in relatively small devices, which is attractive for quantum simulation and for protocols in secure communication that rely on strong scrambling.6

Quantum devices operating close to the chaotic regime are natural sources of pseudo-random unitaries. These are central ingredients for cryptographic protocols, decoupling theorems, and randomized benchmarking. The challenge is to harvest this randomness in a controlled way without letting chaos destroy the delicate structure needed for computation.6

Methods and Models Used

The results above are grounded in a variety of complementary methods. Classical simulations of transmon arrays by Börner et al. derive Hamilton’s equations for coupled pendula representing transmons and numerically integrate them to compute Lyapunov exponents and Poincaré sections.5

On the quantum side, diagnostics for systems of up to ten transmons use exact diagonalization to obtain many body eigenstates and inverse participation ratios, with agreement between regions of large Lyapunov exponent and delocalized eigenstates providing a concrete quantum classical correspondence.5

Field theoretic effective models developed by Altland and Sonner construct a nonlinear sigma model describing low energy “Goldstone” modes associated with broken causal symmetry, reproducing random matrix spectral statistics, including the characteristic dip, ramp, and plateau of the spectral form factor, from a microscopic standpoint.2

At the circuit level, Leone et al. analyze random Clifford circuits supplemented with non-Clifford gates and, by computing higher order out of time order correlators and fluctuations of entanglement purity, demonstrate that only when the number of non-Clifford gates scales linearly with the number of qubits does the circuit exhibit genuinely chaotic, Haar like behaviour.6

Across these approaches, common diagnostics emerge, including entanglement entropy, spectral statistics, out of time order correlators and Lyapunov exponents, each offering a different window onto the same underlying phenomenon of quantum chaos.2

What’s Next?

The realization that quantum chaos may emerge earlier than expected opens several research directions. Classical chaos simulations can guide the design of quantum chips so that qubit frequencies, couplings, and layouts avoid chaotic resonances in the computational energy window. Quantum error correction will need to account for correlated and system wide noise, rather than assuming only local errors.3

Similar studies on trapped ions, Rydberg arrays, and cold atom simulators can test whether this behaviour is generic, while theory aims to link early operator growth and scrambling with late effective descriptions of chaos. Overall, quantum chaos is already relevant in present devices, and controlling it will be crucial for the future of quantum technologies.

References and Further Readings

- Bishop, R. C., An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamics: Classical and Quantum; IOP Publishing, 2025.

- Altland, A.; Sonner, J., Late Time Physics of Holographic Quantum Chaos. SciPost Physics 2021, 11, 034.

- Mok, W.-K.; Haug, T.; Shaw, A. L.; Endres, M.; Preskill, J., Optimal Conversion from Classical to Quantum Randomness Via Quantum Chaos. Physical Review Letters 2025, 134, 180403.

- Lim, C.; Matirko, K.; Polkovnikov, A.; Flynn, M. O., Defining Classical and Quantum Chaos through Adiabatic Transformations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.01927 2024, 10.

- Börner, S.-D.; Berke, C.; DiVincenzo, D. P.; Trebst, S.; Altland, A., Classical Chaos in Quantum Computers. Physical Review Research 2024, 6, 033128.

- Leone, L.; Oliviero, S. F.; Zhou, Y.; Hamma, A., Quantum Chaos Is Quantum. Quantum 2021, 5, 453.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.