Researchers at TU Wien have integrated quantum physics with general relativity, revealing significant departures from established models. The study was published in Physical Review D.

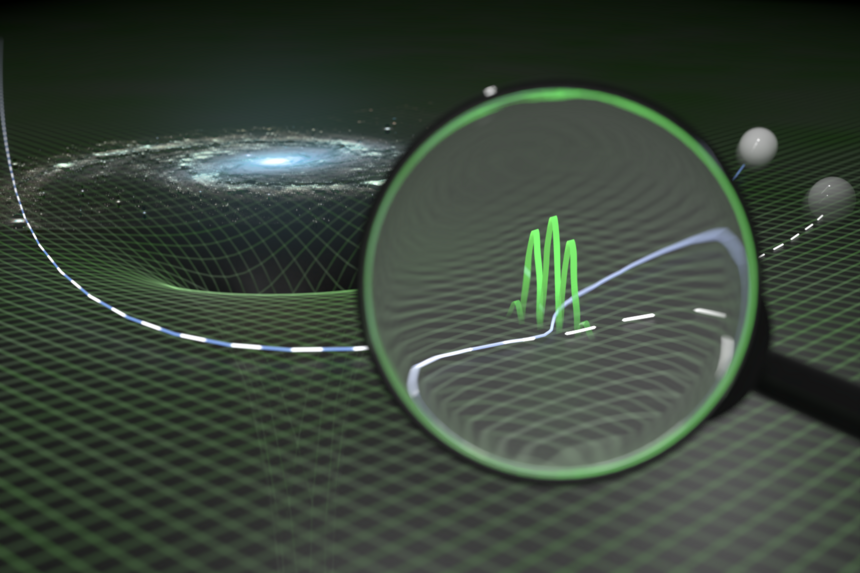

Quantum-Geodesics. Large masses, such as galaxies, curve space-time. Objects move along a geodesic. If we take into account that space-time itself has quantum properties, deviations arise (dashed line vs. solid line). Image Credit: Oliver Diekmann, TU Wien

Quantum-Geodesics. Large masses, such as galaxies, curve space-time. Objects move along a geodesic. If we take into account that space-time itself has quantum properties, deviations arise (dashed line vs. solid line). Image Credit: Oliver Diekmann, TU Wien

The unification of particle physics and gravitation stands as a paramount objective in physics, often termed its "Holy Grail." Quantum theory masterfully explains the world of microscopic particles, whereas Einstein's general theory of relativity governs gravitational phenomena. Despite their individual successes, these two foundational theories of theoretical physics remain incompatible, resisting a cohesive integration.

Numerous theoretical frameworks, including string theory, loop quantum gravity, canonical quantum gravity, and asymptotically safe gravity, propose pathways to this unification, each possessing distinct advantages and limitations. A critical void has been the absence of testable predictions for quantifiable observations and empirical evidence to validate which theory most accurately reflects reality. A recent investigation conducted at TU Wien potentially advances us toward achieving this challenging objective.

Cinderella and Quantum Gravity

It’s a bit like the Cinderella fairy tale. There are several candidates, but only one of them can be the princess we are looking for. Only when the prince finds the slipper can he identify the real Cinderella. In quantum gravity, we have unfortunately not yet found such a slipper, an observable that clearly tells us which theory is the right one.

Benjamin Koch, Institute for Theoretical Physics, TU Wien

To establish measurable criteria for theory assessment, a process likened to determining the correct 'shoe size', the team investigated the concept of geodesics.

“Practically everything we know about general relativity relies on the interpretation of geodesics,” explained Benjamin Koch.

A geodesic is the shortest connection between two points – on a flat plane that’s simply a straight line, whereas on curved surfaces things become more complicated.

Benjamin Koch, Institute for Theoretical Physics, TU Wien

Consider moving from the North Pole to the South Pole on a sphere's surface; the most direct route is a semicircle.

Relativity theory establishes an inseparable link between space and time, creating a four-dimensional spacetime. This spacetime is warped by massive objects like stars or planets. General relativity attributes Earth's orbit around the Sun to the Sun's mass distorting space and time, which then curves the Earth's natural path (geodesic) into an approximately circular trajectory.

The Quantum Version of Geodesics

The metric, which quantifies the degree of spacetime curvature, defines the trajectory of these geodesics.

“We can now try to apply the rules of quantum physics to this metric. In quantum physics, particles have neither a precisely defined position nor a precisely defined momentum. Instead, both are described by probability distributions. The more precisely you know one of them, the more fuzzy and uncertain the other becomes,” said Benjamin Koch.

Mirroring the quantum physics approach, where particle positions and momenta are substituted by a more complex mathematical entity, a quantized wave function, the metric of general relativity can similarly be considered for a quantized replacement. Consequently, spacetime curvature loses its exact definition at every point, instead being represented by a quantum-mechanically blurred form of this quantity.

This Approach Leads to Major Mathematical Challenges

Benjamin Koch, in collaboration with his PhD student Ali Riahinia and Angel Rincón (Czech Republic), has developed a novel method for quantizing the metric. This approach addresses the significant special case of a spherically symmetric gravitational field that remains constant over time.

This type of field can, for example, describe the gravity of the Sun.

“Next, we wanted to calculate how a small object behaves in this gravitational field – but using the quantum version of this metric. In doing so, we realized that one has to be very careful – for instance, whether one is allowed to replace the metric operator by its expectation value, a kind of quantum average of the spacetime curvature. We were able to answer this question mathematically,” said Koch.

The derived q-desic equation, analogous to classical geodesics, allows for the inference of the metric's quantum properties.

“This equation shows that in a quantum spacetime, particles do not always move exactly along the shortest path between two points, as the classical geodesic equation would predict,” said Benjamin Koch.

This is achieved by observing the trajectories of freely moving particles in spacetime, exemplified by phenomena such as an apple falling toward Earth in outer space.

Shoe Size 10(-35) or Rather 10(+21)?

The differences between a q-desic and a classical geodesic are minimal when considering only ordinary gravitation, which is the weakest of the known fundamental forces.

“In this case, we end up with deviations of only about 10(-35) meters – far too small to ever be observed in any experiment,” said Benjamin Koch.

General relativity, however, incorporates the cosmological constant, also referred to as "dark energy," a crucial quantity responsible for the accelerated expansion of the universe on the largest scales. This cosmological constant can also be included in the q-desic equation.

“And when we did that, we were in for a surprise. The q-desics now differ significantly from the geodesics one would obtain in the usual way without quantum physics,” reported Benjamin Koch.

Deviations are observed at both extremely small and extremely large distances. While those at small distances are projected to remain unobservable, substantial discrepancies are anticipated at length scales approximating 10(21) m.

“In between, for example, when it comes to the Earth’s orbit around the Sun, there is practically no difference. But on very large cosmological scales – precisely where major puzzles of general relativity remain unsolved – there is a clear difference between the particle trajectories predicted by the q-desic equation and those obtained from unquantized general relativity,” said Benjamin Koch.

A New Perspective on Observational Data

The study introduces a novel mathematical approach for linking quantum theory and gravitation. Its primary significance lies in enabling new methods for comparing the theory with observations.

“At first, I would not have expected quantum corrections on large scales to produce such dramatic changes. We now need to analyze this in more detail, of course, but it gives us hope that by further developing this approach we can gain a new, and observationally well testable, insight into important cosmic phenomena – such as the still unsolved puzzle of the rotation speeds of spiral galaxies,” said Benjamin Koch.

An observable has been identified that provides a definitive criterion for distinguishing between viable and incorrect approaches to quantum gravity. The subsequent task is to determine which theoretical framework accurately accommodates this empirical finding.

Journal Reference:

Koch, B., et al. (2025) Geodesics in quantum gravity. Physical Review D. DOI:10.1103/w1sd-v69d. https://journals.aps.org/prd/abstract/10.1103/w1sd-v69d