Feb 22 2017

Almost all the light we see in the universe comes from stars which form inside dense clouds of gas in the interstellar medium. The rate at which they form (referred to as the star formation rate, or SFR) depends on the reserves of gas in the galaxies and the physical conditions in the interstellar medium, which vary as the stars themselves evolve. Measuring the star formation rate is hence key to understand the formation and evolution of galaxies.

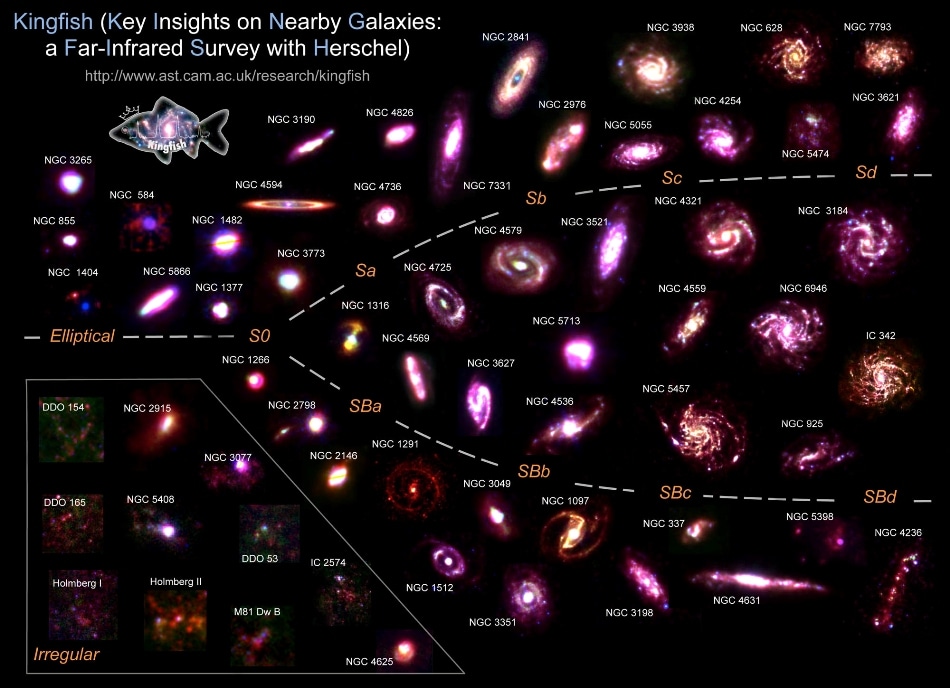

The radio observations were based on the KINGFISH (“Key Insights on Nearby Galaxies: a Far-Infrared Survey with Herschel”) sample of galaxies. The compilation shows composite infrared images of these galaxies created from Spitzer (SINGS) and Herschel (KINGFISH) observations. Credit: Maud Galametz.

The radio observations were based on the KINGFISH (“Key Insights on Nearby Galaxies: a Far-Infrared Survey with Herschel”) sample of galaxies. The compilation shows composite infrared images of these galaxies created from Spitzer (SINGS) and Herschel (KINGFISH) observations. Credit: Maud Galametz.

Until now, a variety of observations at different wavelengths have been performed to calculate the SFR, each with its advantages and disadvantages. As the most commonly used SFR tracers, the visible and the ultraviolet emission can be partly absorbed by interstellar dust. This has motivated the use of hybrid tracers, which combine two or more different emissions, including the infrared, which can help to correct this dust absorption. However, the use of these tracers is often uncertain because other sources or mechanisms which are not related to the formation of massive stars can intervene and lead to confusion.

Now, an international research team led by the IAC astrophysicist Fatemeh Tabatabaei has made a detailed analysis of the spectral energy distribution of a sample of galaxies, and has been able to measure, for the first time, the energy they emit within the frequency range of 1-10 Gigahertz which can be used to know their star formation rates. "We have used" explains this researcher "the radio emission because, in previous studies, a tight correlation was detected between the radio and the infrared emission, covering a range of more than four orders of magnitude". In order to explain this correlation, more detailed studies were needed to understand the energy sources and processes which produce the radio emission observed in the galaxies.

"We decided within the research group to make studies of galaxies from the KINGFISH sample (Key Insights on Nearby Galaxies: a Far-Infrared Survey with Herschel) at a series of radio frequencies", recalls Eva Schinnerer from the Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie (MPIA) in Heidelberg, Germany. The final sample consists of 52 galaxies with very diverse properties. "As a single dish, the 100-m Effelsberg telescope with its high sensitivity is the ideal instrument to receive reliable radio fluxes of weak extended objects like galaxies", explains Marita Krause from the Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie (MPIfR) in Bonn, Germany, who was in charge of the radio observations of those galaxies with the Effelsberg radio telescope. "We named it the KINGFISHER project, meaning KINGFISH galaxies Emitting in Radio."

The results of this project, published today in The Astrophysical Journal, show that the 1-10 Gigahertz radio emission used is an ideal star formation tracer for several reasons. Firstly, the interstellar dust does not attenuate or absorb radiation at these frequencies; secondly, it is emitted by massive stars during several phases of their formation, from young stellar objects to HII regions (zones of ionized gas) and supernova remnants, and finally, there is no need to combine it with any other tracer. For these reasons, measurements in the chosen range are a more rigorous way to estimate the formation rate of massive stars than the tracers traditionally used.

This study also clarifies the nature of the feedback processes occurring due to star formation activity, which are key in evolution of galaxies. "By differentiating the origins of the radio continuum, we could infer that the cosmic ray electrons (a component of the interstellar medium) are younger and more energetic in galaxies with higher star formation rates, which can cause powerful winds and outflows and have important consequences in regulation of star formation", explains Fatemeh Tabatabaei.