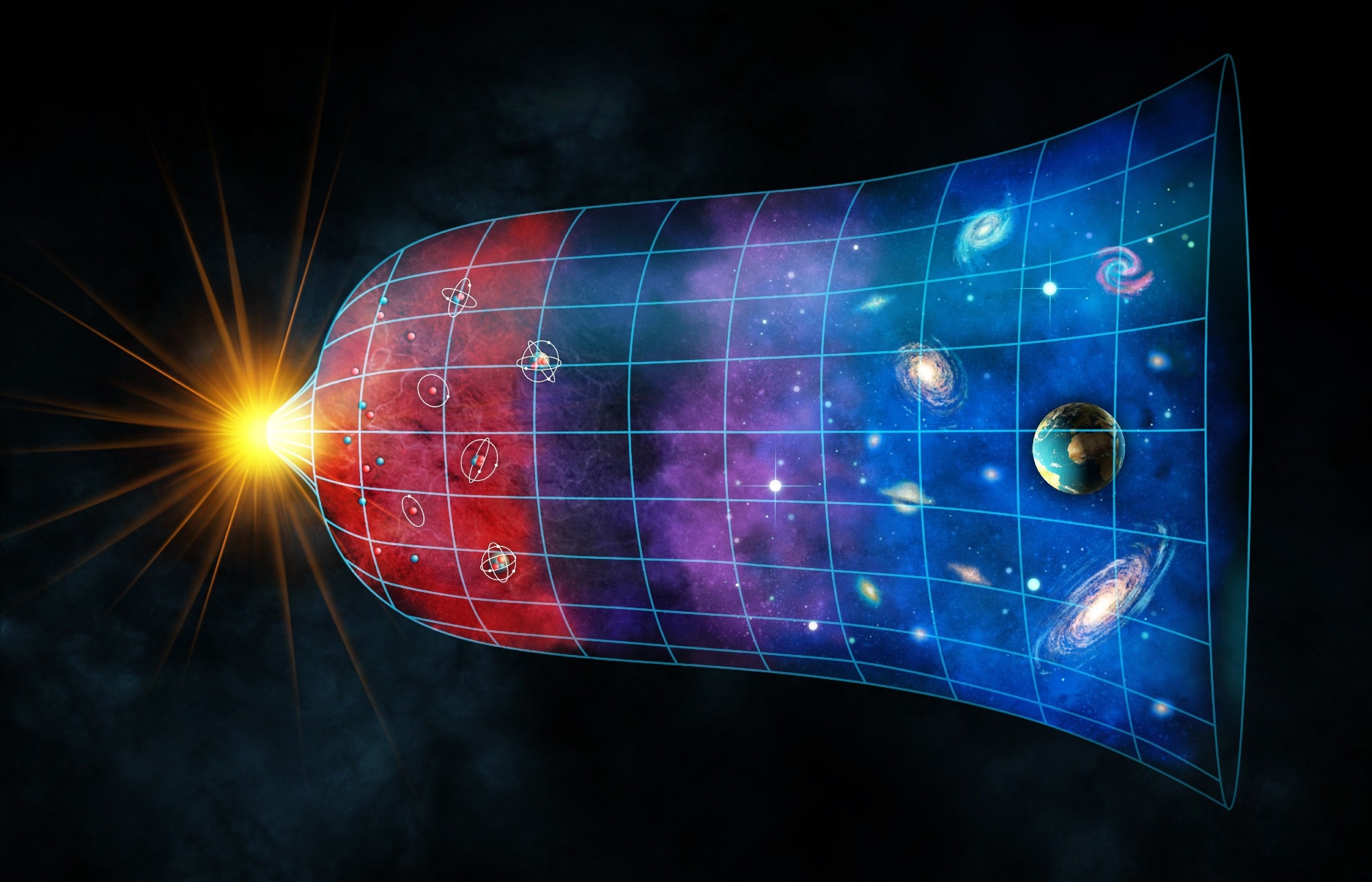

The Big Bang marks the origin of space, time, and energy. The universe began in an extremely hot, dense state and has been expanding and cooling ever since. Matter, radiation, and the fundamental physical laws emerged together as the universe evolved from its earliest instants. This article explores the first three minutes after the Big Bang, how the initial light elements formed in the early universe, and the physical processes that governed nucleosynthesis during these critical moments.

Image Credit: Andrea Danti/Shutterstock.com

The Universe’s First Moments

Before stars, galaxies, or planets existed, the universe generated hydrogen, helium, and trace amounts of other light elements. This process, called Big Bang nucleosynthesis, occurred within the first few minutes after the universe's origin. Understanding what happened during this short window provides a picture of the early universe and sets the basis for all later cosmic structure. During this brief period, the temperature and density dropped enough to allow protons and neutrons to combine into atomic nuclei. Once this window closed, the universe expanded and cooled too quickly for further large-scale element formation. Everything heavier than lithium would have to wait for stars and stellar explosions billions of years later.1

What Happened in the First Seconds?

The initial physical conditions of the universe changed rapidly over extremely short timescales. Modern physics categorizes the timeline of the early universe into key events, each defined by a drop in temperature and a change in the state of matter.2, 3

At the very beginning, during the Planck epoch (10-43 to 10-32 seconds), the four fundamental forces of nature, including gravity, electromagnetism, and the strong and weak nuclear forces, were likely unified into a single force. Then the universe underwent an inflationary period of exponential growth where space itself expanded faster than the speed of light. This smoothed out the distribution of energy.2, 3

When the universe cooled to approximately 1015 Kelvin, it was filled with a mixture of elementary particles called a quark-gluon plasma. At these temperatures, quarks could not yet bind together to form more complex particles. However, with further expansion and the temperature drop, quarks began to group into triplets, forming the first protons and neutrons.

The temperature had fallen to about 10 billion Kelvin in one second of the Big Bang. The universe transitioned from a hot, dense plasma to cool enough to form protons and neutrons in 1 second to 3 minutes, which was the critical window for nucleosynthesis. If the universe had stayed this hot for longer, the particles would have been too energetic to stick together, and if it had cooled too quickly, they never would have met.2, 3

Download the PDF of this article

The Physics Behind Element Formation

The formation of elements in the early universe depended on temperature, density, and the balance between protons and neutrons. Neutrons and protons converted into each other through weak nuclear interactions at very high temperatures. When the universe cooled, these reactions slowed and eventually froze out, leaving slightly fewer neutrons than protons. Neutrons are unstable on their own, so some decayed before they could be incorporated into nuclei.

Nuclear fusion began when the universe was about three minutes old and cool enough. Protons and neutrons combined to form deuterium. Deuterium then fused into helium-3 and helium-4. Helium-4, containing two protons and two neutrons, is stable, which explains why most surviving neutrons ended up bound in helium nuclei.3, 4

The reason only light elements formed during this period, and heavier elements did not, is the rapid expansion of the universe. The density and temperature dropped too quickly for complex nuclear reactions to continue long enough to produce heavier nuclei beyond the lightest elements. As a result, Big Bang nucleosynthesis ended quickly, locking in the primordial elemental abundances.3, 4

Evidence for Big Bang Nucleosynthesis

A key source of evidence comes from observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the faint radiation left over from when the universe became transparent about 380,000 years after the Big Bang. Measurements of the CMB provide precise values for the universe’s baryon density, which directly influences nucleosynthesis calculations.5, 6

Observations of ancient gas clouds located between galaxies also help, as these clouds have experienced minimal stellar processing, making them good approximations of primordial matter. Their deuterium and helium abundances closely match theoretical predictions.

Space missions such as WMAP and Planck have played a major role in refining measurements of cosmological parameters. The agreement between predicted and observed abundances of hydrogen and helium supports our understanding of nucleosynthesis in the early universe.5, 6

Unsolved Questions and Ongoing Research

There is one notable discrepancy in BBN. Theoretical models predict a certain amount of Lithium-7 should have produced. However, when we observe old stars, we see significantly less, about a factor of three lower, lithium than expected.

Nucleosynthesis also informs broader questions in cosmology. Because elemental abundances depend on the density of ordinary matter, they help constrain the amount of baryonic matter in the universe. When combined with other observations, this shows the dominance of dark matter, which does not participate in nucleosynthesis but influences cosmic structure.

Future observations may help resolve these issues. The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) can study extremely old stars and distant galaxies, which may improve measurements of early chemical abundances. Upcoming experiments such as CMB-S4 aim to provide even more precise data on the early universe, and will refine constraints on expansion rates and matter content.7, 8

The Role of Quantum Physics and Particle Interactions

Processes in the early universe were governed by quantum physics and particle interactions at high energies. Quantum field theory describes how particles were created, annihilated, and transformed during these early moments.

An important aspect is the asymmetry between matter and antimatter. Although the Big Bang should have produced equal amounts of both, the observable universe is dominated by matter. Subtle differences in particle interactions, known as CP violation, may have favored matter slightly, allowing it to survive after most matter-antimatter pairs annihilated.

Weak nuclear interactions also played an important role as they controlled the conversion rates between protons and neutrons and influenced the neutron-to-proton ratio. Studying nucleosynthesis provides a way to probe physics beyond the Standard Model of particle physics. Any deviation between predictions and observations could point to new particles or forces that were active in the early universe.9

Future Developments in Observational Cosmology

The earliest phases of the universe are only partially understood as we still lack a complete theory that unifies gravity with quantum mechanics, and the exact nature of inflation and baryogenesis.

Future research will focus on precision measurements of elemental ratios, improved modeling of nuclear reactions, and deeper observations of the early cosmos. These efforts aim to test competing theories of inflation, better understand dark matter, and clarify the origins of matter.

We explore the lithium imbalance here

References

- Steigman, G. (2003). Big bang nucleosynthesis: Probing the first 20 minutes. arXiv preprint astro-ph. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.astro-ph/0307244

- Rafelski, J., Birrell, J., Grayson, C., Steinmetz, A., & Tao Yang, C. (2025). Quarks to cosmos: particles and plasma in cosmological evolution. The European Physical Journal Special Topics. https://doi.org/10.1140/epjs/s11734-025-01470-w

- Allahverdi, R., Amin, M. A., Berlin, A., Bernal, N., Byrnes, C. T., Delos, M. S., ... & Watson, S. (2020). The first three seconds: a review of possible expansion histories of the early universe. arXiv preprint arXiv. https://doi.org/10.21105/astro.2006.16182

- Shima, T. (2024). Isotopes: How did they all begin? Primordial nucleosynthesis: experimental study of the roles of neutrons. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10967-024-09422-9

- Aghanim, N. (2020). Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/201833910

- Kislitsyn, P. A., Balashev, S. A., Murphy, M. T., Ledoux, C., Noterdaeme, P., & Ivanchik, A. V. (2024). A new precise determination of the primordial abundance of deuterium: Measurement in the metal-poor sub-DLA system at z= 3.42 towards quasar J 1332+ 0052. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. https://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stae248

- Singh, V., Bhowmick, D., & Basu, D. N. (2024). Re-examining the Lithium abundance problem in Big-Bang nucleosynthesis. Astroparticle Physics. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.astropartphys.2024.102995

- CMB-S4 Collaboration. (2021). CMB-S4 Preliminary Baseline Design Report. https://indico.cmb-s4.org/event/3/attachments/5/51/PBDR_v0.1.pdf

- Keus, V., & Kolb, E. W. (2025). Baryogenesis from primordial CP violation. Journal of High Energy Physics. https://doi.org/10.1007/JHEP07(2025)156

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.