Superconductors have electrical resistance that becomes zero below a specific threshold temperature, allowing a persistent current flow without energy loss. In classical physics, this behavior is not very obvious because electrons normally repel one another. The explanation for this behavior lies in a special paired state of electrons called Cooper pairs. These pairs form the foundation of superconductivity and are central to both conventional BCS theory and modern studies of high-temperature materials.1, 2, 3

Image Credit: SeniMelihat/Shutterstock.com

The Physics Behind Cooper Pair Formation

In a normal conductor, electrons scatter from ions and imperfections, producing heat and resistance. Whereas in a superconductor, electrons instead pair through an indirect attraction which is mediated by lattice vibrations known as phonons. An electron passing through the lattice slightly distorts local ions, and this distortion can attract another electron.

This phonon-mediated attraction becomes stable only below a critical temperature, where thermal agitation is low. The resulting Cooper pairs condense into a collective quantum state, moving without the scattering events that usually cause resistance. This behavior is described by Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory, which remains the most successful microscopic description of conventional superconductivity.3, 4

Download the PDF of the article

The Importance of Cooper Pairs: From Theory to Technology

The formation of Cooper pairs accounts for two key properties observed in superconductors:

Zero Electrical Resistance

Cooper pairs form a condensate that moves collectively. Scattering events that normally disrupt electron flow are suppressed because the state is coherent. Current therefore flows without energy loss.1

Meissner Effect

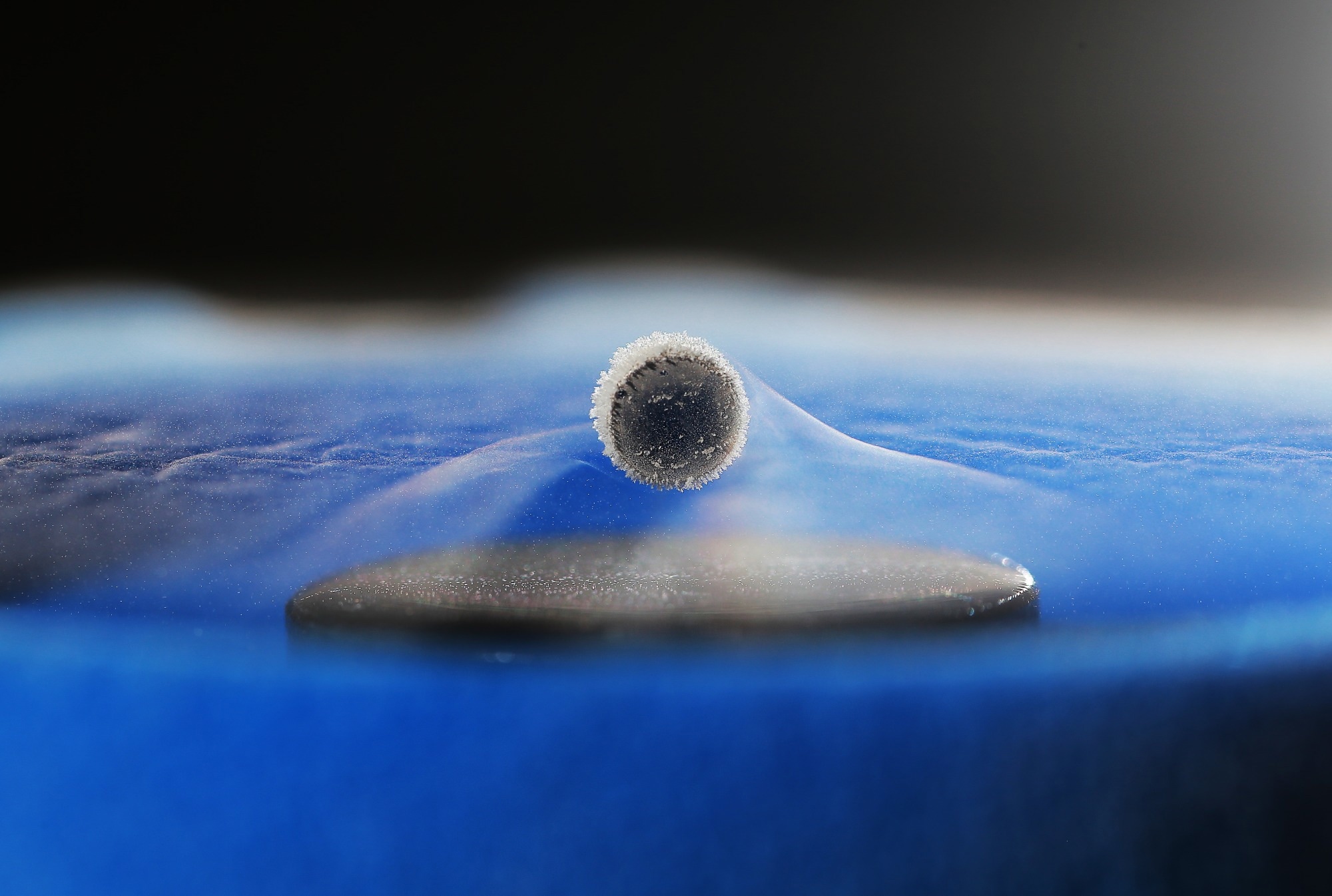

Superconductors expel magnetic fields from their interior. This expulsion arises due to the rigidity of the superconducting wavefunction and is a direct consequence of Cooper pair condensation.5

Both features originate from the quantum nature of electron pairing. Without Cooper pairs, superconductivity does not appear.

Cooper Pairs in Industry and Quantum Devices

Superconductivity is already embedded in several major technologies:

MRI Systems

High-field magnets used in medical imaging rely on superconducting coils. The stability and efficiency of these systems depend on persistent currents created by Cooper pairs.

Particle Accelerators

Large-scale accelerators use superconducting magnets to guide beams. The ability to maintain strong fields with minimal power loss comes from zero-resistance behaviour.6

SQUIDs

Superconducting quantum interference devices measure extremely small magnetic fields using phase differences between Cooper pairs across Josephson junctions.

Quantum Computing

Superconducting qubits, used by Google’s Sycamore and IBM, exploit tunnelling of Cooper pairs through Josephson junctions to generate stable quantum states. Their coherence properties reflect the collective nature of the superconducting condensate.

These applications demonstrate how Cooper pairs enable precision, efficiency, and stability across multiple sectors.1, 7

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their advantages, superconductors face several significant limitations that continue to challenge researchers and engineers. One of the most persistent hurdles is the need for extremely low temperatures. Even so-called "high-temperature" superconductors, like cuprates, must be cooled with liquid nitrogen to reach their critical temperature, still far below room temperature.8

Another complication arises from the unconventional pairing mechanisms observed in many of these materials. Systems such as cuprates, iron pnictides, and certain graphene-based structures exhibit d-wave or other anisotropic pairing symmetries that aren't fully captured by traditional BCS theory. This lack of a comprehensive theoretical framework makes it harder to predict or design new superconducting materials.9, 10

Material complexity is also a major concern. Many high-Tc superconductors are chemically intricate, brittle, and highly sensitive to structural disorder, making them difficult to manufacture and integrate into practical devices.

Finally, while hydrogen-rich hydrides have achieved critical temperatures above 200 K, they only exhibit superconductivity under extreme pressures, on the order of megabars. These conditions are far from practical for real-world applications, limiting the immediate utility of these promising materials.11

Understanding Cooper pairs in these systems, including when pairing is driven by magnetic rather than phononic interactions, remains an open challenge. However, many superconductors do not fit neatly into the BCS framework. Cuprates, iron pnictides, and twisted bilayer graphene exhibit pairing that cannot be explained by phonons alone. Instead, magnetic fluctuations and strong electronic correlations play a major role in binding electrons into Cooper pairs.12 This motivates ongoing research into unconventional mechanisms and universal pairing models.

What’s Next?

High-pressure hydride superconductors remain a major focus because they show strong electron–phonon coupling and very high critical temperatures, although their stability outside extreme pressures is still a limitation.13 Two-dimensional systems such as twisted bilayer graphene offer another route, where superconductivity appears at specific rotational alignments and seems to arise from electronic correlations and magnetic fluctuations rather than phonon-driven pairing.10 Nickelate superconductors also contribute to this landscape; their structural similarities to cuprates, combined with distinct electronic properties, provide opportunities to examine unconventional pairing mechanisms. In parallel, computational materials design is becoming more important, as it supports the prediction of potential superconductors and helps analyse how electron–phonon interactions and correlation effects influence pairing behaviour. These areas collectively outline the current research trajectory and indicate how progress in understanding both conventional and unconventional pairing mechanisms may influence applications in energy, sensing, and quantum technologies.

Want to learn more about particle pairing? It's all here

References and Further Reading

- Wu, H. (2024). Recent development in high temperature superconductor: Principle, materials, and applications. Applied and Computational Engineering. https://doi.org/10.54254/2755-2721/63/20241015

- Kresin, V. Z., Ovchinnikov, S. G., & Wolf, S. A. (2021). Superconducting State: Mechanisms and Materials. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/OSO/9780198845331.001.0001

- Combescot, R. (2022). Superconductivity. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108560184

- Bennemann, K. H. (2024). Superconductivity: BCS theory (pp. 657–669). Elsevier BV. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-323-90800-9.00255-9

- Song, Y. (2025). A Review of the Fundamental Principles and Research Progress in Superconductors. Highlights in Science Engineering and Technology, 149, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.54097/fdg1wg54

- Sharma, R. G. (2015). Superconductivity: Basics and Applications to Magnets. https://www.amazon.com/Superconductivity-Applications-Magnets-Springer-Materials/dp/3319137123

- Rogalla, H., & Kes, P. H. (2011). 100 years of superconductivity. CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/B11312

- Bussmann-Holder, A., & Keller, H. U. (2020). High-temperature superconductors: underlying physics and applications. Zeitschrift Für Naturforschung B, 75, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1515/ZNB-2019-0103

- Keimer, B., Kivelson, S. A., Norman, M. R., Uchida, S., & Zaanen, J. (2015). From quantum matter to high-temperature superconductivity in copper oxides. Nature, 518(7538), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1038/NATURE14165

- Oh, M., Nuckolls, K. P., Wong, D., Lee, R. L., Liu, X., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T., & Yazdani, A. (2021). Evidence for unconventional superconductivity in twisted bilayer graphene. Nature, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41586-021-04121-X

- Eremets, M. I. (2022). Superconductivity at High Pressure (pp. 368–386). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108806145.015

- Maiti, S., & Chubukov, A. V. (2013). Superconductivity from repulsive interaction. 1550, 3–73. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4818400

- Pasupuleti, M. K. (2025). Room-Temperature Superconductors: The Key to an Energy Revolution. 63–75. https://doi.org/10.62311/nesx/32299

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.