In a recent study in Nature, a research team from Columbia University and the University of Texas at Austin has made a groundbreaking observation: a superfluid, which typically remains in perpetual motion, has been observed to come to a halt. The study was led by physicists Cory Dean from Columbia University and Jia Li from the University of Texas at Austin.

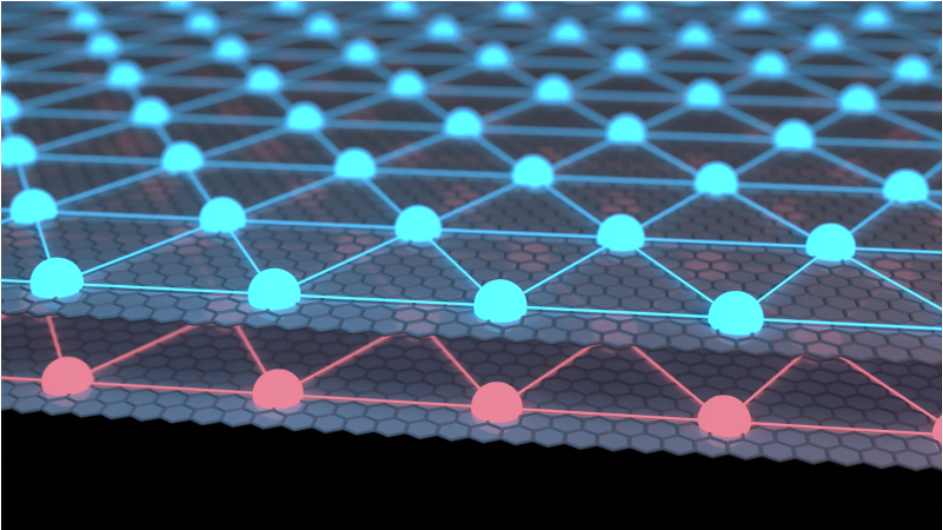

Image Credit: Dean Lab, Columbia University

Image Credit: Dean Lab, Columbia University

When ordinary matter cools, it typically shifts from a gas to a liquid, and with further cooling, becomes a solid. Quantum matter, however, behaves in strikingly different ways. In the early 20th century, scientists discovered that cooling helium doesn’t just lead to a standard liquid, but turns it into a superfluid. This unusual state of matter flows without any energy loss and displays other surprising quantum properties, including the ability to climb the walls of its container.

What occurs when a superfluid is cooled even further? This question has perplexed physicists since they began exploring it fifty years ago.

For the first time, we’ve witnessed a superfluid transition into what seems to be a supersolid.

Cory Dean, Study Lead, Columbia University

This phenomenon is similar to the process of water freezing into ice, but it occurs at the quantum level.

Supersolids represent the anticipated quantum equivalent of a classical solid, characterized by a stable arrangement of atoms within a repeating crystal lattice. Interestingly, supersolids can simultaneously exhibit properties of both liquids and solids: they are crystalline, similar to classical solids, yet are expected to demonstrate the same frictionless flow characteristic of superfluids.

Despite these theoretical predictions, the transition from superfluid to supersolid has not yet been definitively observed in helium or any other naturally occurring materials. In recent years, researchers within the atomic, molecular, and optical (AMO) subfield of physics have created simulated versions of supersolids, employing lasers and optical components to establish what is referred to as a periodic trap. This setup aids in guiding the fluid into a crystal-like formation, reminiscent of Jello being confined within an ice cube tray.

A spontaneously forming supersolid has remained a mystery, contributing to one of the significant unresolved debates in condensed matter physics. This situation persisted until Dean's team, which included Li during his postdoctoral tenure at Columbia and a former Ph.D. student Yihang Zeng (currently an assistant professor at Purdue University), shifted their focus to a naturally occurring crystal: graphene, a single-atom-thick layer of carbon atoms.

Graphene is capable of hosting what are referred to as excitons. These quasiparticles emerge when two-atom-thin sheets of graphene are stacked and manipulated in such a way that one layer possesses an excess of electrons while the other has an excess of holes (which are vacancies created when electrons exit the layer in response to light). The negatively charged electrons and positively charged holes can merge to form excitons. When a strong magnetic field is applied, excitons can transition into a superfluid.

Two-dimensional materials such as graphene have surfaced as promising platforms for investigating and manipulating phenomena such as superfluidity and superconductivity. This is due to the various "knobs" that researchers can adjust, including temperature, electromagnetic fields, and even the spacing between layers, allowing for precise tuning of their properties.

When Dean's team commenced adjusting these knobs to regulate the excitons in their samples, they observed an unexpected correlation between the density of the quasiparticles and temperature. At elevated densities, their excitons exhibited superfluid behavior; however, as the density diminished, they ceased movement and transitioned into insulators. Upon increasing the temperature, superfluidity re-emerged.

Superfluidity is generally regarded as the low-temperature ground state. Observing an insulating phase that melts into a superfluid is unprecedented. This strongly suggests that the low-temperature phase is a highly unusual exciton solid.

Jia Li, Study Lead, University of Texas, Austin

So, is it a supersolid? “We are left to speculate some, as our ability to interrogate insulators stops a little. For now, we’re exploring the boundaries around this insulating state, while building new tools to measure it directly,” explained Dean – their expertise is in transport measurements, and insulators do not transport a current.

The team is also exploring additional layered materials. The excitonic superfluid, and potentially even a supersolid, that emerges in bilayer graphene relies on the presence of a strong magnetic field to form. While alternative systems are more difficult to fabricate into the necessary configurations, they offer a key advantage: the possibility of stabilizing quasiparticles at higher temperatures without the need for an external magnetic field .

The ability to control a superfluid within a 2D material opens up exciting possibilities. Unlike helium, excitons are thousands of times lighter, making it feasible for quantum states like superfluids and supersolids to emerge at much higher temperatures. Although the realization of supersolids remains on the horizon, growing evidence suggests that 2D materials will play a crucial role in helping researchers better understand this elusive quantum phase.

Sources:

Journal Reference:

Zeng, Y., et al. (2026) Observation of a superfluid-to-insulator transition of bilayer excitons. Nature. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09986-w. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09986-w

Columbia University