Mar 22 2016

The lightest few elements in the periodic table formed minutes after the Big Bang. Heavier chemical elements are created by stars, either from nuclear fusion in their interiors or in catastrophic explosions. However, scientists have disagreed for nearly 60 years about how the heaviest elements, such as gold and lead, are manufactured. New observations of a tiny galaxy discovered last year show that these heavy elements are likely left over from rare collisions between two neutron stars. The work is published by Nature.

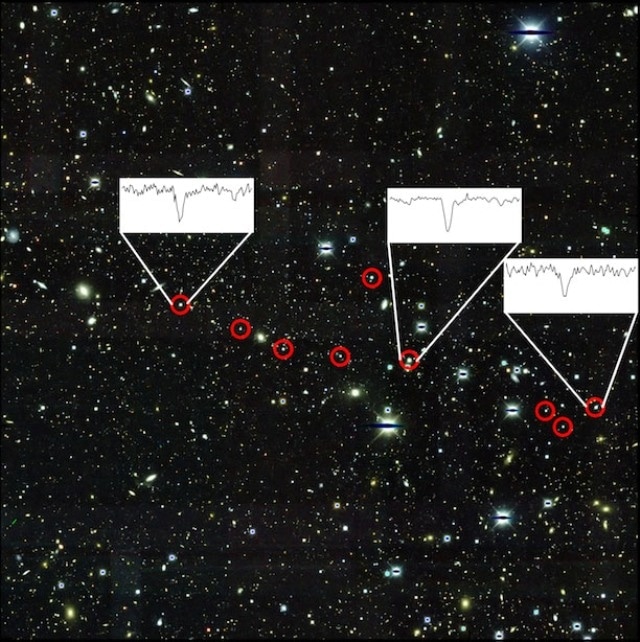

This is an image of Reticulum II obtained by the Dark Energy Survey, using the Blanco 4-meter telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. The nine stars described in the paper are circled in red. The insets show the very strong presence of barium, one of the main neutron capture elements the team observed, in three stars. Background image is courtesy of Dark Energy Survey/Fermilab. Foreground image is courtesy of Alexander Ji, Anna Frebel, Anirudh Chiti, and Josh Simon.

This is an image of Reticulum II obtained by the Dark Energy Survey, using the Blanco 4-meter telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory. The nine stars described in the paper are circled in red. The insets show the very strong presence of barium, one of the main neutron capture elements the team observed, in three stars. Background image is courtesy of Dark Energy Survey/Fermilab. Foreground image is courtesy of Alexander Ji, Anna Frebel, Anirudh Chiti, and Josh Simon.

The new galaxy, called Reticulum II because of its location in the southern constellation Reticulum, commonly known as The Net, is one of the smallest and closest to us known. Its proximity made it a tempting target for a team of astronomers including Carnegie’s Josh Simon, who have been studying the chemical content of nearby galaxies.

“Reticulum II has more stars bright enough for chemical studies than any other ultra-faint dwarf galaxy found so far,” Simon explained.

Such ultra-faint galaxies are relics from the era when the universe’s first stars were born. They orbit our own Milky Way galaxy and their chemical simplicity can help astronomers understand the history of stellar processes dating back to the ancient universe, including element formation.

Many elements are formed by nuclear fusion, in which two atomic nuclei fuse together and release energy, creating a different, heavier atom. But elements heavier than zinc are made by a process called neutron capture, during which an existing element acquires additional neutrons one at a time that then “decay” into protons, changing the makeup of the atom into a new element.

Neutrons can be captured slowly, over long periods of time inside the star, or in a matter of seconds, when a catastrophic event causes a burst of neutrons to bombard an area. Different types of elements are created by each method.

Surprisingly, the team found that seven of Reticulum II’s nine brightest stars contained far more elements produced by rapid neutron captures than have been detected in any other dwarf galaxy.

“These stars have up to a thousand times more neutron capture elements than any other stars observed in similar galaxies,” said lead author Alexander Ji of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Previously, astronomers had been divided over whether such elements are primarily made by supernova explosions or in more exotic cosmic locations, such as merging neutron stars. However, finding so many more heavy elements in one dwarf galaxy than had ever been seen before in others proves that the source of Reticulum II’s neutron capture elements must have been a rare event—much less common than an ordinary supernova. What’s more, the sheer amount of these neutron capture elements in Reticulum II far exceeds what most supernovae can even make.

“Producing rapid neutron capture elements in a neutron star merger explains these observations beautifully,” said co-author Anna Frebel, also of MIT.

Old stars in the Milky Way show a pattern of neutron capture elements similar to that found in Reticulum II. This indicates that the process of making neutron capture elements in larger galaxies is likely the same as it is in dwarf galaxies, suggesting that even the heavy elements on Earth originated in neutron star mergers.

The team expects that observations of more stars in Reticulum II mayImage shed further light on the origin of heavy elements and the formation history of this unique system.

“Because this galaxy is so small, it preserves evidence of ancient rare events incredibly cleanly,” said Simon. “We’re lucky to have found such an important galaxy so close to us.”

Data were gathered using the 6.5-m Magellan telescopes located at Las Campanas Observatory, Chile. This work made use of NASA’s Astrophysics Data System Bibliographic Services and the python libraries numpy, scipy, matplotlib, seaborn, and astropy. This research made use of data products originally obtained with the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), which was constructed by the Dark Energy Survey (DES) collaboration. Funding for the DES Projects has been provided by the DOE and NSF (USA), MISE (Spain), STFC (UK), HEFCE (UK). NCSA (UIUC), KICP (U. Chicago), CCAPP (Ohio State), MIFPA (Texas A&M), CNPQ, FAPERJ, FINEP (Brazil), MINECO (Spain), DFG (Germany) and the collaborating institutions in the Dark Energy Survey, which are Argonne Lab, UC Santa Cruz, University of Cambridge, CIEMAT-Madrid, University of Chicago, University College London, DES-Brazil Consortium, University of Edinburgh, ETH Zurich, Fermilab, University of Illinois, ICE (IEECCSIC), IFAE Barcelona, Lawrence Berkeley Lab, LMU Munchen and the associated Excellence Cluster Universe, University of Michigan, NOAO, University of Nottingham, Ohio State University, University of Pennsylvania, University of Portsmouth, SLAC National Lab, Stanford University, University of Sussex, and Texas A&M University.