Nov 28 2015

It’s prime time for a group of heavy-ion physicists from Rice University, who begin in earnest this week to probe for new details about the physical universe.

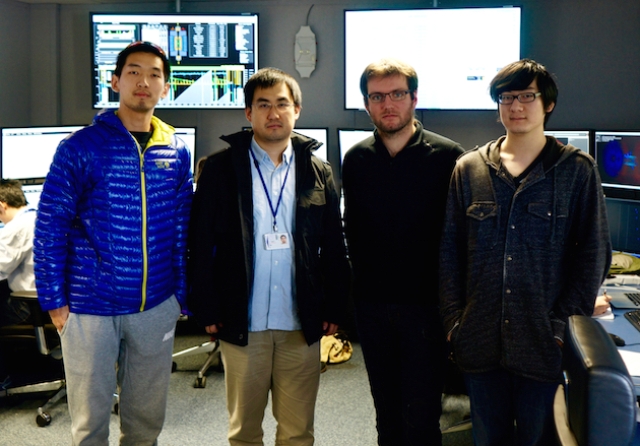

Members of the Rice University team take a break at the Compact Muon Solenoid control room at CERN this week. From left: Zhoudunming Tu, Wei Li, Maxime Guilbaud and Zhenyu Chen.

Members of the Rice University team take a break at the Compact Muon Solenoid control room at CERN this week. From left: Zhoudunming Tu, Wei Li, Maxime Guilbaud and Zhenyu Chen.

Wei Li, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy, is the leader of the group working at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), to which he returned last week. The European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) facility that straddles Switzerland and France restarted earlier this year after a long period of retooling to operate at higher energies.

Those higher energies are now on display in Li’s area of interest, the products created when heavy ions — in this case, lead atoms stripped of their electrons — are collided at nearly the speed of light to produce a quark-gluon plasma, a material not far removed from that believed to exist in the microseconds after the Big Bang.

Li and his team of Rice postdoctoral researcher Maxime Guilbaud and graduate students Zhenyu Chen, Zhoudunming Tu and Michael Northup will monitor real-time data from sensors inside the Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS), one of four major experiments that straddle the 17-mile LHC ring.

The startup means two things for the team. First, they expect to get more finely detailed information about the high-momentum quarks and gluons that scatter from plasmas created by smashing ions together. Quarks and gluons are the elemental particles that make up protons and neutrons.

Second, there are sleepless nights ahead, as the one-month run of collisions happen at all hours, around the clock.

“Both Maxime and Zhenyu are the detector on-call experts, so they have to be available 24 hours a day,” Li said. “We cannot predict when the beam will start, so we have to be ready. They are responsible for two crucial parts of the detector operation, so if there’s a problem, they have to solve it immediately.”

The Rice team designed and installed software that makes real-time decisions about what data to save from the millions of collisions that take place each second of a run, Li said. Data about particles that escape from the plasma are collected by CMS smart sensors designed at Rice.

In this run, Li said the team wants to characterize the detailed properties of quark-gluon plasma with unprecedented precision. “We want to see how energetic quark and gluons behave as they penetrate through the plasma fields,” he said. “It’s a kind of tomography approach in which the quarks and gluons are our probes.” In tomography, penetrating waves are used to analyze the structure of an object of interest, be it a human body or the bottom of the ocean.

“They are fast enough that they can make it out,” he said. “However, as they do, they interact with the quark-gluon plasma and will lose some energy. This is what we are looking for: how they lose energy and how they get disturbed by the presence of the plasma.”

Besides a couple of very fast-moving quarks or gluons, each heavy-ion collision radiates up to about 20,000 other particles, which may provide insight about how they spread from the primordial plasma that contained what became the universe. The speed at which particles escaped is analogous to the mottled background radiation observed at the far reaches of the observable universe today and, by extension, why matter ultimately clumped into stars and planets.

Over the next month, the LHC will collide heavy ions for up to eight hours at a time, after which the beam will be shut down for refueling, Li said. “Once the collisions start, the intensity of the beam drops,” he said. “When it gets too low, the beam is turned off and they refuel as soon as possible. That takes a few hours, and if everything goes well and we’re lucky, we may get data for 12, 14, 16 hours a day.”

Li said while the beam energy has doubled to 5 trillion electron volts, the intensity increased by a factor of 10. “We’re going to have 10 times more collisions during the same period of time, so we can do a lot of studies with much greater precision,” he said.

At the end of the month, the team will begin to work through that mountain of data. “Early next year, our focus will shift to analyzing the data and publishing the physics results,” he said. “When we approach the next run (in late 2016), we’ll switch our priority to preparation.”

Except for a mandatory two-week shutdown at Christmas, there’s little downtime for the team. “We can still work at home but we won’t be able to come into the office,” Li said.

Source: http://www.rice.edu/